Remote Branches

Remote branches are references to the state of branches on your remote repositories. They’re local branches that you can’t move; they’re moved automatically whenever you do any network communication. Remote branches act as bookmarks to remind you where the branches on your remote repositories were the last time you connected to them.

They take the form (remote)/(branch). For instance, if you wanted to see what the master branch on your origin remote looked like as of the last time you communicated with it, you would check the origin/master branch. If you were working on an issue with a partner and they pushed up an iss53 branch, you might have your own local iss53 branch; but the branch on the server would point to the commit at origin/iss53.

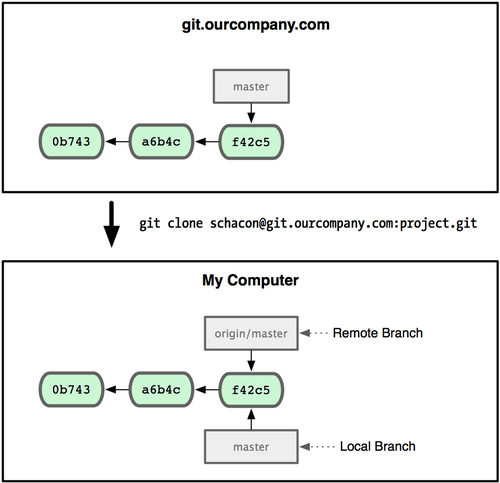

This may be a bit confusing, so let’s look at an example. Let’s say you have a Git server on your network at git.ourcompany.com. If you clone from this, Git automatically names it origin for you, pulls down all its data, creates a pointer to where its master branch is, and names it origin/master locally; and you can’t move it. Git also gives you your own master branch starting at the same place as origin’s master branch, so you have something to work from (see Figure 3-22).

Figure 3-22. A Git clone gives you your own master branch and origin/master pointing to origin’s master branch.

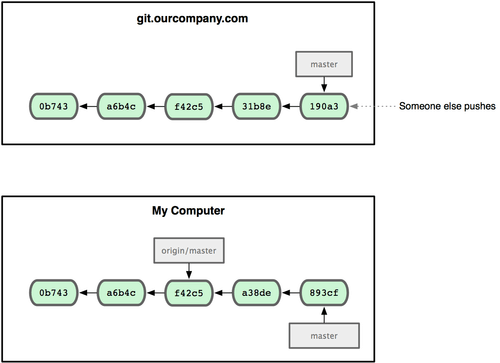

If you do some work on your local master branch, and, in the meantime, someone else pushes to git.ourcompany.com and updates its master branch, then your histories move forward differently. Also, as long as you stay out of contact with your origin server, your origin/master pointer doesn’t move (see Figure 3-23).

Figure 3-23. Working locally and having someone push to your remote server makes each history move forward differently.

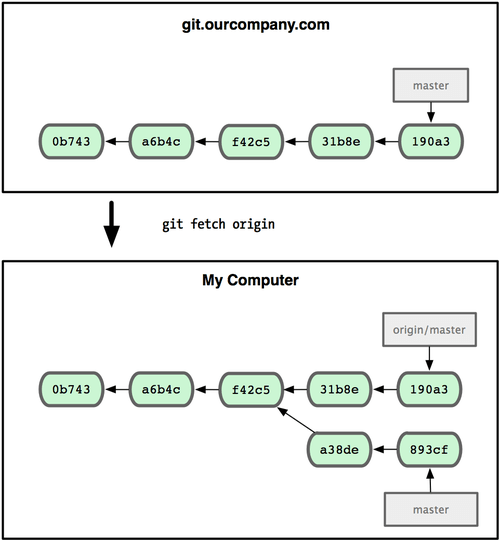

To synchronize your work, you run a git fetch origin command. This command looks up which server origin is (in this case, it’s git.ourcompany.com), fetches any data from it that you don’t yet have, and updates your local database, moving your origin/master pointer to its new, more up-to-date position (see Figure 3-24).

Figure 3-24. The git fetch command updates your remote references.

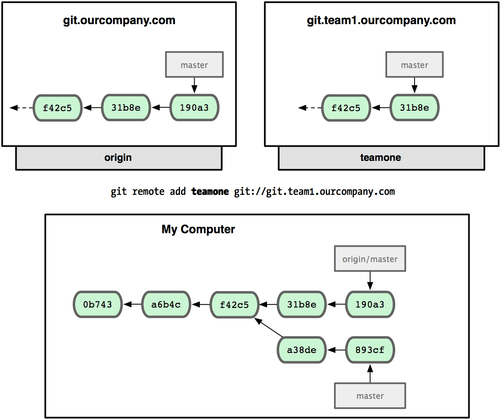

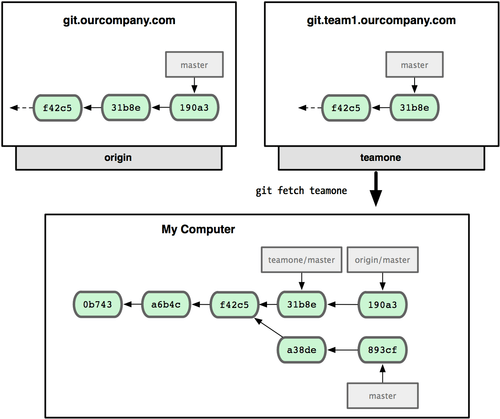

To demonstrate having multiple remote servers and what remote branches for those remote projects look like, let’s assume you have another internal Git server that is used only for development by one of your sprint teams. This server is at git.team1.ourcompany.com. You can add it as a new remote reference to the project you’re currently working on by running the git remote add command as we covered in Chapter 2. Name this remote teamone, which will be your shortname for that whole URL (see Figure 3-25).

Figure 3-25. Adding another server as a remote.

Now, you can run git fetch teamone to fetch everything the remote teamone server has that you don’t have yet. Because that server has a subset of the data your origin server has right now, Git fetches no data but sets a remote branch called teamone/master to point to the commit that teamone has as its master branch (see Figure 3-26).

Figure 3-26. You get a reference to teamone’s master branch position locally.

Pushing

When you want to share a branch with the world, you need to push it up to a remote that you have write access to. Your local branches aren’t automatically synchronized to the remotes you write to — you have to explicitly push the branches you want to share. That way, you can use private branches for work you don’t want to share, and push up only the topic branches you want to collaborate on.

If you have a branch named serverfix that you want to work on with others, you can push it up the same way you pushed your first branch. Run git push (remote) (branch):

$ git push origin serverfix

Counting objects: 20, done.

Compressing objects: 100% (14/14), done.

Writing objects: 100% (15/15), 1.74 KiB, done.

Total 15 (delta 5), reused 0 (delta 0)

To git@github.com:schacon/simplegit.git

* [new branch] serverfix -> serverfix

This is a bit of a shortcut. Git automatically expands the serverfix branchname out to refs/heads/serverfix:refs/heads/serverfix, which means, “Take my serverfix local branch and push it to update the remote’s serverfix branch.” We’ll go over the refs/heads/ part in detail in Chapter 9, but you can generally leave it off. You can also do git push origin serverfix:serverfix, which does the same thing — it says, “Take my serverfix and make it the remote’s serverfix.” You can use this format to push a local branch into a remote branch that is named differently. If you didn’t want it to be called serverfix on the remote, you could instead run git push origin serverfix:awesomebranch to push your local serverfix branch to the awesomebranch branch on the remote project.

The next time one of your collaborators fetches from the server, they will get a reference to where the server’s version of serverfix is under the remote branch origin/serverfix:

$ git fetch origin

remote: Counting objects: 20, done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (14/14), done.

remote: Total 15 (delta 5), reused 0 (delta 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (15/15), done.

From git@github.com:schacon/simplegit

* [new branch] serverfix -> origin/serverfix

It’s important to note that when you do a fetch that brings down new remote branches, you don’t automatically have local, editable copies of them. In other words, in this case, you don’t have a new serverfix branch — you only have an origin/serverfix pointer that you can’t modify.

To merge this work into your current working branch, you can run git merge origin/serverfix. If you want your own serverfix branch that you can work on, you can base it off your remote branch:

$ git checkout -b serverfix origin/serverfix

Branch serverfix set up to track remote branch serverfix from origin.

Switched to a new branch 'serverfix'

This gives you a local branch that you can work on that starts where origin/serverfix is.

Tracking Branches

Checking out a local branch from a remote branch automatically creates what is called a tracking branch. Tracking branches are local branches that have a direct relationship to a remote branch. If you’re on a tracking branch and type git push, Git automatically knows which server and branch to push to. Also, running git pull while on one of these branches fetches all the remote references and then automatically merges in the corresponding remote branch.

When you clone a repository, it generally automatically creates a master branch that tracks origin/master. That’s why git push and git pull work out of the box with no other arguments. However, you can set up other tracking branches if you wish — ones that don’t track branches on origin and don’t track the master branch. The simple case is the example you just saw, running git checkout -b [branch] [remotename]/[branch]. If you have Git version 1.6.2 or later, you can also use the --track shorthand:

$ git checkout --track origin/serverfix

Branch serverfix set up to track remote branch serverfix from origin.

Switched to a new branch 'serverfix'

To set up a local branch with a different name than the remote branch, you can easily use the first version with a different local branch name:

$ git checkout -b sf origin/serverfix

Branch sf set up to track remote branch serverfix from origin.

Switched to a new branch 'sf'

Now, your local branch sf will automatically push to and pull from origin/serverfix.

Deleting Remote Branches

Suppose you’re done with a remote branch — say, you and your collaborators are finished with a feature and have merged it into your remote’s master branch (or whatever branch your stable codeline is in). You can delete a remote branch using the rather obtuse syntax git push [remotename] :[branch]. If you want to delete your serverfix branch from the server, you run the following:

$ git push origin :serverfix

To git@github.com:schacon/simplegit.git

- [deleted] serverfix

Boom. No more branch on your server. You may want to dog-ear this page, because you’ll need that command, and you’ll likely forget the syntax. A way to remember this command is by recalling the git push [remotename] [localbranch]:[remotebranch] syntax that we went over a bit earlier. If you leave off the [localbranch] portion, then you’re basically saying, “Take nothing on my side and make it be [remotebranch].”