Git Attributes

Some of these settings can also be specified for a path, so that Git applies those settings only for a subdirectory or subset of files. These path-specific settings are called Git attributes and are set either in a .gitattributes file in one of your directories (normally the root of your project) or in the .git/info/attributes file if you don’t want the attributes file committed with your project.

Using attributes, you can do things like specify separate merge strategies for individual files or directories in your project, tell Git how to diff non-text files, or have Git filter content before you check it into or out of Git. In this section, you’ll learn about some of the attributes you can set on your paths in your Git project and see a few examples of using this feature in practice.

Binary Files

One cool trick for which you can use Git attributes is telling Git which files are binary (in cases it otherwise may not be able to figure out) and giving Git special instructions about how to handle those files. For instance, some text files may be machine generated and not diffable, whereas some binary files can be diffed — you’ll see how to tell Git which is which.

Identifying Binary Files

Some files look like text files but for all intents and purposes are to be treated as binary data. For instance, Xcode projects on the Mac contain a file that ends in .pbxproj, which is basically a JSON (plain text javascript data format) dataset written out to disk by the IDE that records your build settings and so on. Although it’s technically a text file, because it’s all ASCII, you don’t want to treat it as such because it’s really a lightweight database — you can’t merge the contents if two people changed it, and diffs generally aren’t helpful. The file is meant to be consumed by a machine. In essence, you want to treat it like a binary file.

To tell Git to treat all pbxproj files as binary data, add the following line to your .gitattributes file:

*.pbxproj -crlf -diff

Now, Git won’t try to convert or fix CRLF issues; nor will it try to compute or print a diff for changes in this file when you run git show or git diff on your project. You can also use a built-in macro binary that means -crlf -diff:

*.pbxproj binary

Diffing Binary Files

In Git, you can use the attributes functionality to effectively diff binary files. You do this by telling Git how to convert your binary data to a text format that can be compared via the normal diff. But the question is how do you convert binary data to a text? The best solution is to find some tool that does conversion for your binary format to a text representation. Unfortunately, very few binary formats can be represented as human readable text (imagine trying to convert audio data to a text). If this is the case and you failed to get a text presentation of your file's contents, it's often relatively easy to get a human readable description of that content, or metadata. Metadata won't give you a full representation of your file's content, but in any case it's better than nothing.

We'll make use of the both described approaches to get usable diffs for some widely used binary formats.

Side note: There are different kinds of binary formats with a text content, which are hard to find usable converter for. In such a case you could try to extract a text from your file with the strings program. Some of these files may use an UTF-16 encoding or other "codepages" and strings won’t find anything useful in there. Your mileage may vary. However, strings is available on most Mac and Linux systems, so it may be a good first try to do this with many binary formats.

MS Word files

First, you’ll use the described technique to solve one of the most annoying problems known to humanity: version-controlling Word documents. Everyone knows that Word is the most horrific editor around; but, oddly, everyone uses it. If you want to version-control Word documents, you can stick them in a Git repository and commit every once in a while; but what good does that do? If you run git diff normally, you only see something like this:

$ git diff

diff --git a/chapter1.doc b/chapter1.doc

index 88839c4..4afcb7c 100644

Binary files a/chapter1.doc and b/chapter1.doc differ

You can’t directly compare two versions unless you check them out and scan them manually, right? It turns out you can do this fairly well using Git attributes. Put the following line in your .gitattributes file:

*.doc diff=word

This tells Git that any file that matches this pattern (.doc) should use the "word" filter when you try to view a diff that contains changes. What is the "word" filter? You have to set it up. Here you’ll configure Git to use the catdoc program, which was written specifically for extracting text from a binary MS Word documents (you can get it from http://www.wagner.pp.ru/~vitus/software/catdoc/), to convert Word documents into readable text files, which it will then diff properly:

$ git config diff.word.textconv catdoc

This command adds a section to your .git/config that looks like this:

[diff "word"]

textconv = catdoc

Now Git knows that if it tries to do a diff between two snapshots, and any of the files end in .doc, it should run those files through the "word" filter, which is defined as the catdoc program. This effectively makes nice text-based versions of your Word files before attempting to diff them.

Here’s an example. I put Chapter 1 of this book into Git, added some text to a paragraph, and saved the document. Then, I ran git diff to see what changed:

$ git diff

diff --git a/chapter1.doc b/chapter1.doc

index c1c8a0a..b93c9e4 100644

--- a/chapter1.doc

+++ b/chapter1.doc

@@ -128,7 +128,7 @@ and data size)

Since its birth in 2005, Git has evolved and matured to be easy to use

and yet retain these initial qualities. It’s incredibly fast, it’s

very efficient with large projects, and it has an incredible branching

-system for non-linear development.

+system for non-linear development (See Chapter 3).

Git successfully and succinctly tells me that I added the string "(See Chapter 3)", which is correct. Works perfectly!

OpenDocument Text files

The same approach that we used for MS Word files (*.doc) can be used for OpenDocument Text files (*.odt) created by OpenOffice.org.

Add the following line to your .gitattributes file:

*.odt diff=odt

Now set up the odt diff filter in .git/config:

[diff "odt"]

binary = true

textconv = /usr/local/bin/odt-to-txt

OpenDocument files are actually zip’ped directories containing multiple files (the content in an XML format, stylesheets, images, etc.). We’ll need to write a script to extract the content and return it as plain text. Create a file /usr/local/bin/odt-to-txt (you are free to put it into a different directory) with the following content:

#! /usr/bin/env perl

# Simplistic OpenDocument Text (.odt) to plain text converter.

# Author: Philipp Kempgen

if (! defined($ARGV[0])) {

print STDERR "No filename given!\n";

print STDERR "Usage: $0 filename\n";

exit 1;

}

my $content = '';

open my $fh, '-|', 'unzip', '-qq', '-p', $ARGV[0], 'content.xml' or die $!;

{

local $/ = undef; # slurp mode

$content = <$fh>;

}

close $fh;

$_ = $content;

s/<text:span\b[^>]*>//g; # remove spans

s/<text:h\b[^>]*>/\n\n***** /g; # headers

s/<text:list-item\b[^>]*>\s*<text:p\b[^>]*>/\n -- /g; # list items

s/<text:list\b[^>]*>/\n\n/g; # lists

s/<text:p\b[^>]*>/\n /g; # paragraphs

s/<[^>]+>//g; # remove all XML tags

s/\n{2,}/\n\n/g; # remove multiple blank lines

s/\A\n+//; # remove leading blank lines

print "\n", $_, "\n\n";

And make it executable

chmod +x /usr/local/bin/odt-to-txt

Now git diff will be able to tell you what changed in .odt files.

Image files

Another interesting problem you can solve this way involves diffing image files. One way to do this is to run PNG files through a filter that extracts their EXIF information — metadata that is recorded with most image formats. If you download and install the exiftool program, you can use it to convert your images into text about the metadata, so at least the diff will show you a textual representation of any changes that happened:

$ echo '*.png diff=exif' >> .gitattributes

$ git config diff.exif.textconv exiftool

If you replace an image in your project and run git diff, you see something like this:

diff --git a/image.png b/image.png

index 88839c4..4afcb7c 100644

--- a/image.png

+++ b/image.png

@@ -1,12 +1,12 @@

ExifTool Version Number : 7.74

-File Size : 70 kB

-File Modification Date/Time : 2009:04:17 10:12:35-07:00

+File Size : 94 kB

+File Modification Date/Time : 2009:04:21 07:02:43-07:00

File Type : PNG

MIME Type : image/png

-Image Width : 1058

-Image Height : 889

+Image Width : 1056

+Image Height : 827

Bit Depth : 8

Color Type : RGB with Alpha

You can easily see that the file size and image dimensions have both changed.

Keyword Expansion

SVN- or CVS-style keyword expansion is often requested by developers used to those systems. The main problem with this in Git is that you can’t modify a file with information about the commit after you’ve committed, because Git checksums the file first. However, you can inject text into a file when it’s checked out and remove it again before it’s added to a commit. Git attributes offers you two ways to do this.

First, you can inject the SHA-1 checksum of a blob into an $Id$ field in the file automatically. If you set this attribute on a file or set of files, then the next time you check out that branch, Git will replace that field with the SHA-1 of the blob. It’s important to notice that it isn’t the SHA of the commit, but of the blob itself:

$ echo '*.txt ident' >> .gitattributes

$ echo '$Id$' > test.txt

The next time you check out this file, Git injects the SHA of the blob:

$ rm test.txt

$ git checkout -- test.txt

$ cat test.txt

$Id: 42812b7653c7b88933f8a9d6cad0ca16714b9bb3 $

However, that result is of limited use. If you’ve used keyword substitution in CVS or Subversion, you can include a datestamp — the SHA isn’t all that helpful, because it’s fairly random and you can’t tell if one SHA is older or newer than another.

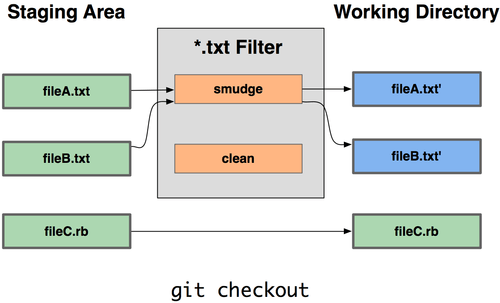

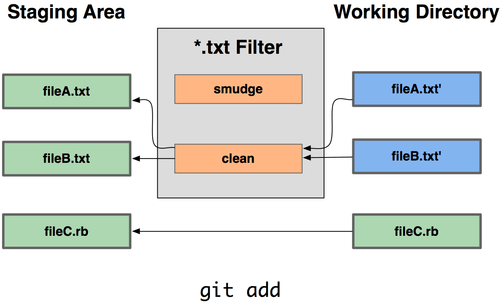

It turns out that you can write your own filters for doing substitutions in files on commit/checkout. These are the "clean" and "smudge" filters. In the .gitattributes file, you can set a filter for particular paths and then set up scripts that will process files just before they’re checked out ("smudge", see Figure 7-2) and just before they’re committed ("clean", see Figure 7-3). These filters can be set to do all sorts of fun things.

Figure 7-2. The “smudge” filter is run on checkout.

Figure 7-3. The “clean” filter is run when files are staged.

The original commit message for this functionality gives a simple example of running all your C source code through the indent program before committing. You can set it up by setting the filter attribute in your .gitattributes file to filter *.c files with the "indent" filter:

*.c filter=indent

Then, tell Git what the "indent" filter does on smudge and clean:

$ git config --global filter.indent.clean indent

$ git config --global filter.indent.smudge cat

In this case, when you commit files that match *.c, Git will run them through the indent program before it commits them and then run them through the cat program before it checks them back out onto disk. The cat program is basically a no-op: it spits out the same data that it gets in. This combination effectively filters all C source code files through indent before committing.

Another interesting example gets $Date$ keyword expansion, RCS style. To do this properly, you need a small script that takes a filename, figures out the last commit date for this project, and inserts the date into the file. Here is a small Ruby script that does that:

#! /usr/bin/env ruby

data = STDIN.read

last_date = `git log --pretty=format:"%ad" -1`

puts data.gsub('$Date$', '$Date: ' + last_date.to_s + '$')

All the script does is get the latest commit date from the git log command, stick that into any $Date$ strings it sees in stdin, and print the results — it should be simple to do in whatever language you’re most comfortable in. You can name this file expand_date and put it in your path. Now, you need to set up a filter in Git (call it dater) and tell it to use your expand_date filter to smudge the files on checkout. You’ll use a Perl expression to clean that up on commit:

$ git config filter.dater.smudge expand_date

$ git config filter.dater.clean 'perl -pe "s/\\\$Date[^\\\$]*\\\$/\\\$Date\\\$/"'

This Perl snippet strips out anything it sees in a $Date$ string, to get back to where you started. Now that your filter is ready, you can test it by setting up a file with your $Date$ keyword and then setting up a Git attribute for that file that engages the new filter:

$ echo '# $Date$' > date_test.txt

$ echo 'date*.txt filter=dater' >> .gitattributes

If you commit those changes and check out the file again, you see the keyword properly substituted:

$ git add date_test.txt .gitattributes

$ git commit -m "Testing date expansion in Git"

$ rm date_test.txt

$ git checkout date_test.txt

$ cat date_test.txt

# $Date: Tue Apr 21 07:26:52 2009 -0700$

You can see how powerful this technique can be for customized applications. You have to be careful, though, because the .gitattributes file is committed and passed around with the project but the driver (in this case, dater) isn’t; so, it won’t work everywhere. When you design these filters, they should be able to fail gracefully and have the project still work properly.

Exporting Your Repository

Git attribute data also allows you to do some interesting things when exporting an archive of your project.

export-ignore

You can tell Git not to export certain files or directories when generating an archive. If there is a subdirectory or file that you don’t want to include in your archive file but that you do want checked into your project, you can determine those files via the export-ignore attribute.

For example, say you have some test files in a test/ subdirectory, and it doesn’t make sense to include them in the tarball export of your project. You can add the following line to your Git attributes file:

test/ export-ignore

Now, when you run git archive to create a tarball of your project, that directory won’t be included in the archive.

export-subst

Another thing you can do for your archives is some simple keyword substitution. Git lets you put the string $Format:$ in any file with any of the --pretty=format formatting shortcodes, many of which you saw in Chapter 2. For instance, if you want to include a file named LAST_COMMIT in your project, and the last commit date was automatically injected into it when git archive ran, you can set up the file like this:

$ echo 'Last commit date: $Format:%cd$' > LAST_COMMIT

$ echo "LAST_COMMIT export-subst" >> .gitattributes

$ git add LAST_COMMIT .gitattributes

$ git commit -am 'adding LAST_COMMIT file for archives'

When you run git archive, the contents of that file when people open the archive file will look like this:

$ cat LAST_COMMIT

Last commit date: $Format:Tue Apr 21 08:38:48 2009 -0700$

Merge Strategies

You can also use Git attributes to tell Git to use different merge strategies for specific files in your project. One very useful option is to tell Git to not try to merge specific files when they have conflicts, but rather to use your side of the merge over someone else’s.

This is helpful if a branch in your project has diverged or is specialized, but you want to be able to merge changes back in from it, and you want to ignore certain files. Say you have a database settings file called database.xml that is different in two branches, and you want to merge in your other branch without messing up the database file. You can set up an attribute like this:

database.xml merge=ours

If you merge in the other branch, instead of having merge conflicts with the database.xml file, you see something like this:

$ git merge topic

Auto-merging database.xml

Merge made by recursive.

In this case, database.xml stays at whatever version you originally had.