What a Branch Is

To really understand the way Git does branching, we need to take a step back and examine how Git stores its data. As you may remember from Chapter 1, Git doesn’t store data as a series of changesets or deltas, but instead as a series of snapshots.

When you commit in Git, Git stores a commit object that contains a pointer to the snapshot of the content you staged, the author and message metadata, and zero or more pointers to the commit or commits that were the direct parents of this commit: zero parents for the first commit, one parent for a normal commit, and multiple parents for a commit that results from a merge of two or more branches.

To visualize this, let’s assume that you have a directory containing three files, and you stage them all and commit. Staging the files checksums each one (the SHA-1 hash we mentioned in Chapter 1), stores that version of the file in the Git repository (Git refers to them as blobs), and adds that checksum to the staging area:

$ git add README test.rb LICENSE

$ git commit -m 'initial commit of my project'

Running git commit checksums all project directories and stores them as tree objects in the Git repository. Git then creates a commit object that has the metadata and a pointer to the root project tree object so it can re-create that snapshot when needed.

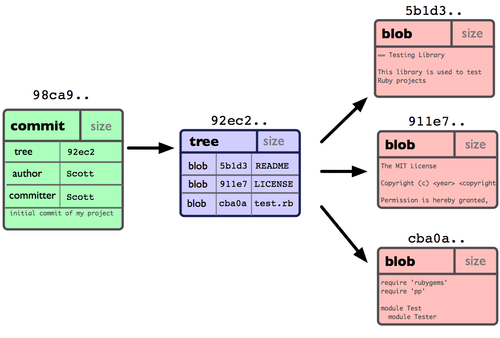

Your Git repository now contains five objects: one blob for the contents of each of your three files, one tree that lists the contents of the directory and specifies which file names are stored as which blobs, and one commit with the pointer to that root tree and all the commit metadata. Conceptually, the data in your Git repository looks something like Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Single commit repository data.

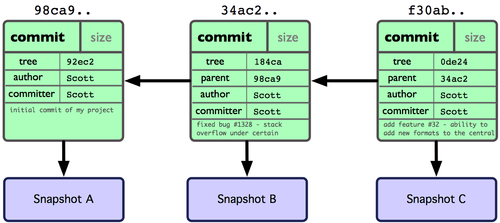

If you make some changes and commit again, the next commit stores a pointer to the commit that came immediately before it. After two more commits, your history might look something like Figure 3-2.

Figure 3-2. Git object data for multiple commits.

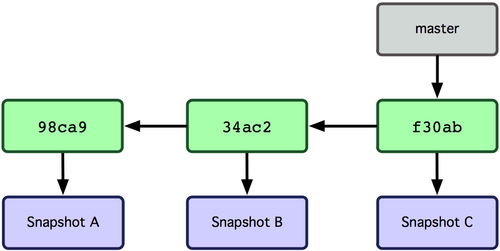

A branch in Git is simply a lightweight movable pointer to one of these commits. The default branch name in Git is master. As you initially make commits, you’re given a master branch that points to the last commit you made. Every time you commit, it moves forward automatically.

Figure 3-3. Branch pointing into the commit data’s history.

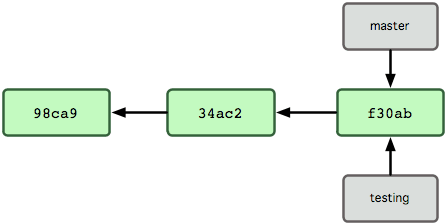

What happens if you create a new branch? Well, doing so creates a new pointer for you to move around. Let’s say you create a new branch called testing. You do this with the git branch command:

$ git branch testing

This creates a new pointer at the same commit you’re currently on (see Figure 3-4).

Figure 3-4. Multiple branches pointing into the commit’s data history.

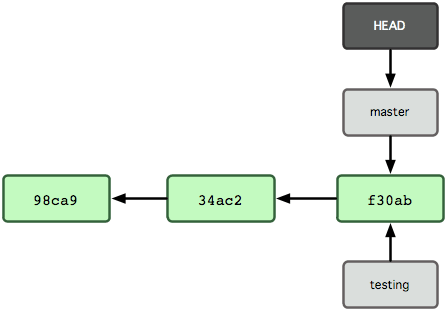

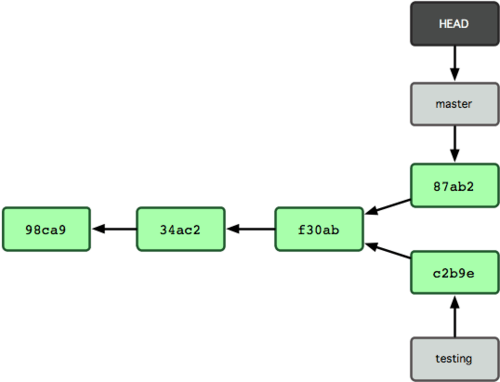

How does Git know what branch you’re currently on? It keeps a special pointer called HEAD. Note that this is a lot different than the concept of HEAD in other VCSs you may be used to, such as Subversion or CVS. In Git, this is a pointer to the local branch you’re currently on. In this case, you’re still on master. The git branch command only created a new branch — it didn’t switch to that branch (see Figure 3-5).

Figure 3-5. HEAD file pointing to the branch you’re on.

To switch to an existing branch, you run the git checkout command. Let’s switch to the new testing branch:

$ git checkout testing

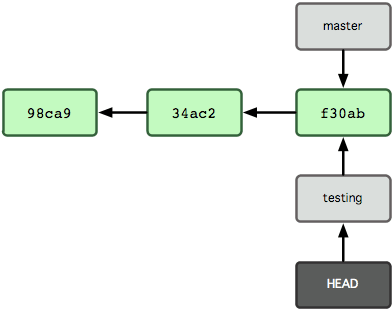

This moves HEAD to point to the testing branch (see Figure 3-6).

Figure 3-6. HEAD points to another branch when you switch branches.

What is the significance of that? Well, let’s do another commit:

$ vim test.rb

$ git commit -a -m 'made a change'

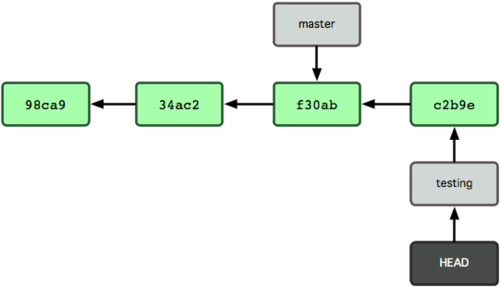

Figure 3-7 illustrates the result.

Figure 3-7. The branch that HEAD points to moves forward with each commit.

This is interesting, because now your testing branch has moved forward, but your master branch still points to the commit you were on when you ran git checkout to switch branches. Let’s switch back to the master branch:

$ git checkout master

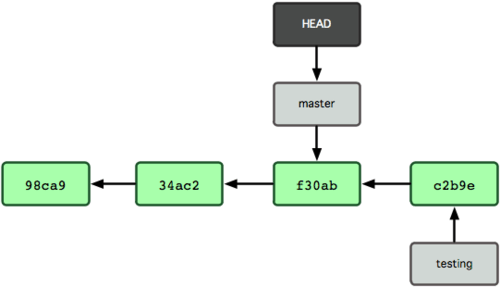

Figure 3-8 shows the result.

Figure 3-8. HEAD moves to another branch on a checkout.

That command did two things. It moved the HEAD pointer back to point to the master branch, and it reverted the files in your working directory back to the snapshot that master points to. This also means the changes you make from this point forward will diverge from an older version of the project. It essentially rewinds the work you’ve done in your testing branch temporarily so you can go in a different direction.

Let’s make a few changes and commit again:

$ vim test.rb

$ git commit -a -m 'made other changes'

Now your project history has diverged (see Figure 3-9). You created and switched to a branch, did some work on it, and then switched back to your main branch and did other work. Both of those changes are isolated in separate branches: you can switch back and forth between the branches and merge them together when you’re ready. And you did all that with simple branch and checkout commands.

Figure 3-9. The branch histories have diverged.

Because a branch in Git is in actuality a simple file that contains the 40 character SHA-1 checksum of the commit it points to, branches are cheap to create and destroy. Creating a new branch is as quick and simple as writing 41 bytes to a file (40 characters and a newline).

This is in sharp contrast to the way most VCS tools branch, which involves copying all of the project’s files into a second directory. This can take several seconds or even minutes, depending on the size of the project, whereas in Git the process is always instantaneous. Also, because we’re recording the parents when we commit, finding a proper merge base for merging is automatically done for us and is generally very easy to do. These features help encourage developers to create and use branches often.

Let’s see why you should do so.